In the quiet landscape where the Sim Corder Harrison Mill stands, time seems to pause. The mill, with its weathered wood and iron fixtures, carries stories of engineering brilliance that date back to a time when technology meant turning water into motion. This structure did more than process grain. It challenged what early engineers thought was possible. It brought engineering innovation to rural life, blending simplicity with function in a way that still inspires today.

When people visit the mill now, they see more than a preserved building. They know how a flowing stream became a power source. They see how structure and mechanics are combined in harmony. Every beam, gear, and wheel tells a story of how innovation shaped survival and success.

A New Way to Use Water

Before electricity became common, water was a dependable force. The Sim Corder Harrison Mill took full advantage of this resource. Its builders saw potential in the nearby stream. They designed a waterwheel that could convert flowing water into movement. That movement powered the machinery inside, enabling grain to be ground without manual labor or fire-based energy.

This wasn’t the first mill to use water, but it did so more efficiently. The wheel was built to work in all seasons, even when the water level dropped. Engineers placed gates and channels to control flow, adjusting pressure as needed. That level of control meant the mill could run for more days in the year, making it more productive and reliable than others at the time.

Form and Function in Harmony

The mill’s exterior looks simple, but its design reflects thoughtful planning. The wooden frame rests on a strong stone base. It holds up well in storms and heavy winds. The builders knew how to balance weight, choose materials that would last, and shape them by hand. This was not just construction. It was engineering, refined through trial and success.

Inside, the layout made work easier. Grain entered at the top and moved downward. Gravity did much of the work, pulling it from the hopper to the grinder and then into storage. Workers didn’t need to carry heavy loads up and down stairs. The design saved time and effort while increasing safety. It proved that good design could improve everyday tasks.

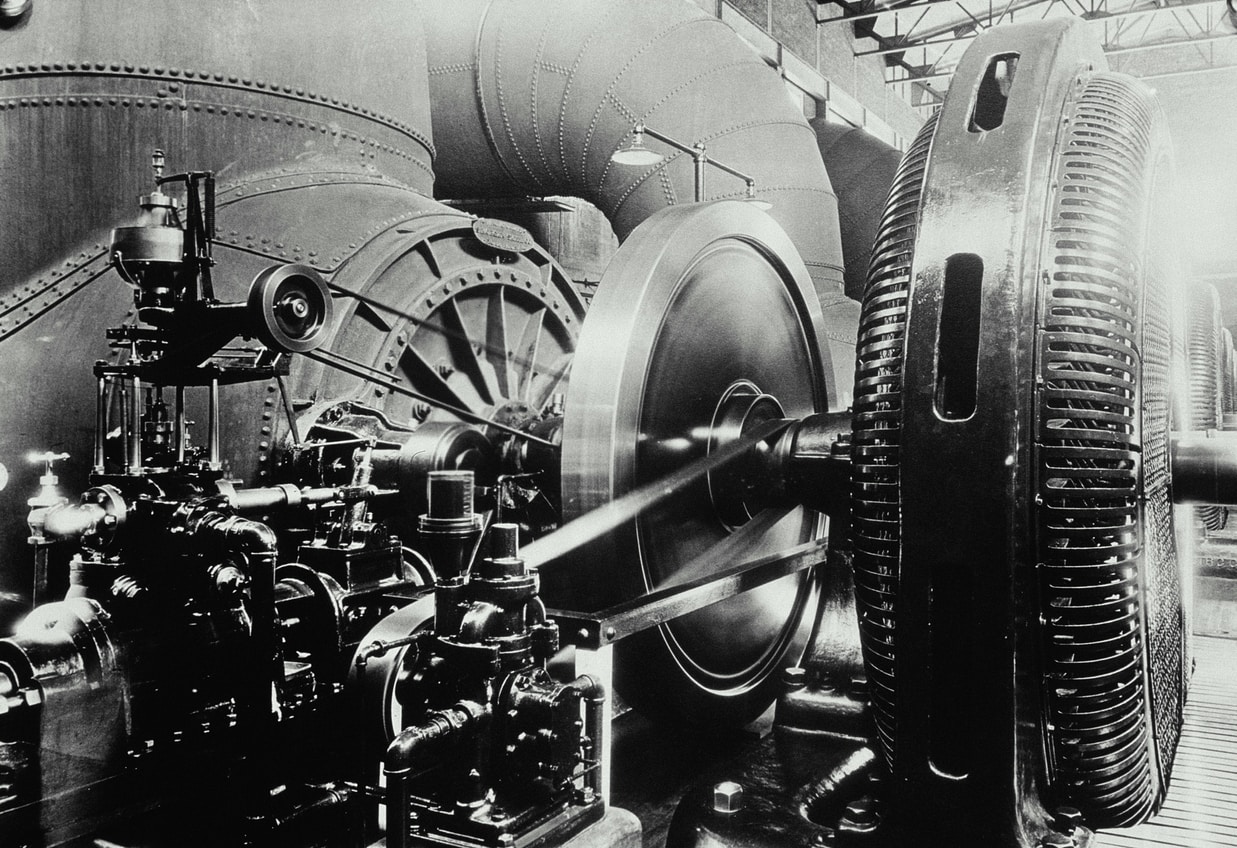

Machines That Kept Moving

At the heart of the mill were machines powered by the waterwheel. Gears, belts, and shafts transferred motion from the wheel to the grinders and sifters. Each piece connected with care. Nothing was random. Engineers understood how friction, pressure, and balance worked. They shaped gears to fit together perfectly and placed pulleys where the tension stayed even.

These systems ran for hours each day. Maintenance was easy because of smart planning. Workers could reach worn parts without disassembling the entire machine. When a belt needed replacing, it took minutes. The mill stayed in motion, day after day. This kind of efficiency was rare. It helped the mill stay active for decades without major redesigns.

Building for the Long Term

The builders did not expect the mill to last a few years. They built it to serve generations. They chose timber that resisted rot. Every choice added strength and life to the mill.

The stone foundation mattered, too. It kept the wood above ground, safe from floods. The stones were tightly locked together, without mortar, allowing water to pass without damage. This method came from deep knowledge of the land and weather. The result was a structure that could stand through snow, rain, heat, and cold without major repairs.

A Tool for the Community

The mill was not just a machine. It was part of daily life for farmers and families in the area. People brought their harvests to be ground into flour or meal. They saved time and got better results than with hand tools. This helped local farms grow and made food production more consistent. It was a place that made work easier and faster.

But it also became a place to gather. While waiting for grain, people talked and shared stories. News spread, plans were made, and friendships grew. The mill helped build a stronger community. It gave people a reason to come together, making it more than just a building. It was a shared space with lasting value.

Innovation Without Excess

What makes the Sim Corder Harrison Mill impressive is how little it needed to do so much. There were no engines or computers. There were no wires or plastics, just wood, stone, water, and human skill. But the result was a system that worked better than many larger, more complex machines of its time.

The mill didn’t waste materials. Every part had a purpose. The gears turned only when needed. The waterwheel used only as much flow as required. The building stayed cool in summer and dry in winter, thanks to smart window and vent placement. This engineering approach, “do more with less,” is still valuable today.

Lessons for the Future

Today’s engineers can learn from the mill. It shows how to make systems that last. It proves that careful planning and local knowledge can solve big problems. The mill reminds us that great ideas come from watching, testing, and building with purpose.

Preserving the mill has helped keep these lessons alive. Artisans use traditional methods to repair it. Historians document its design. Visitors see how it worked and why it mattered. Schools use it as a teaching tool. And through all of this, the mill continues to do what it was built for: share knowledge, help people, and inspire new ways of thinking.

Still Turning, Still Teaching

The Sim Corder Harrison Mill remains a powerful example of what early engineering could achieve. It solved real problems in smart ways. It stood the test of time, not just by luck, but by design. Each beam and gear reflects a choice made with care, guided by experience and need.

As modern life moves faster and becomes more complex, the mill stands quietly as a reminder. Innovation does not have to be loud or high-tech. It can be simple, steady, and shaped by the world around it. The Sim Corder Harrison Mill redefined engineering not by changing everything, but by doing the basics better than anyone else.