The Sim Corder/Harrison Mill stands as a living testament to human ingenuity and industrial brilliance. Built in an era when mechanical power was derived from nature rather than machines, it remains a remarkable symbol of early engineering mastery. The mill not only transformed water into motion but also turned ambition into progress, driving the local economy and inspiring generations of inventors.

This masterpiece of early American engineering demonstrates how innovation can emerge from observation and resourcefulness. Every beam, gear, and water channel was designed with precision, proving that practical knowledge and craftsmanship could produce technology capable of enduring centuries. The Sim Corder/Harrison Mill is more than an old industrial relic—it is a story of human determination, creative problem-solving, and respect for nature’s power.

The Mechanics of Natural Power

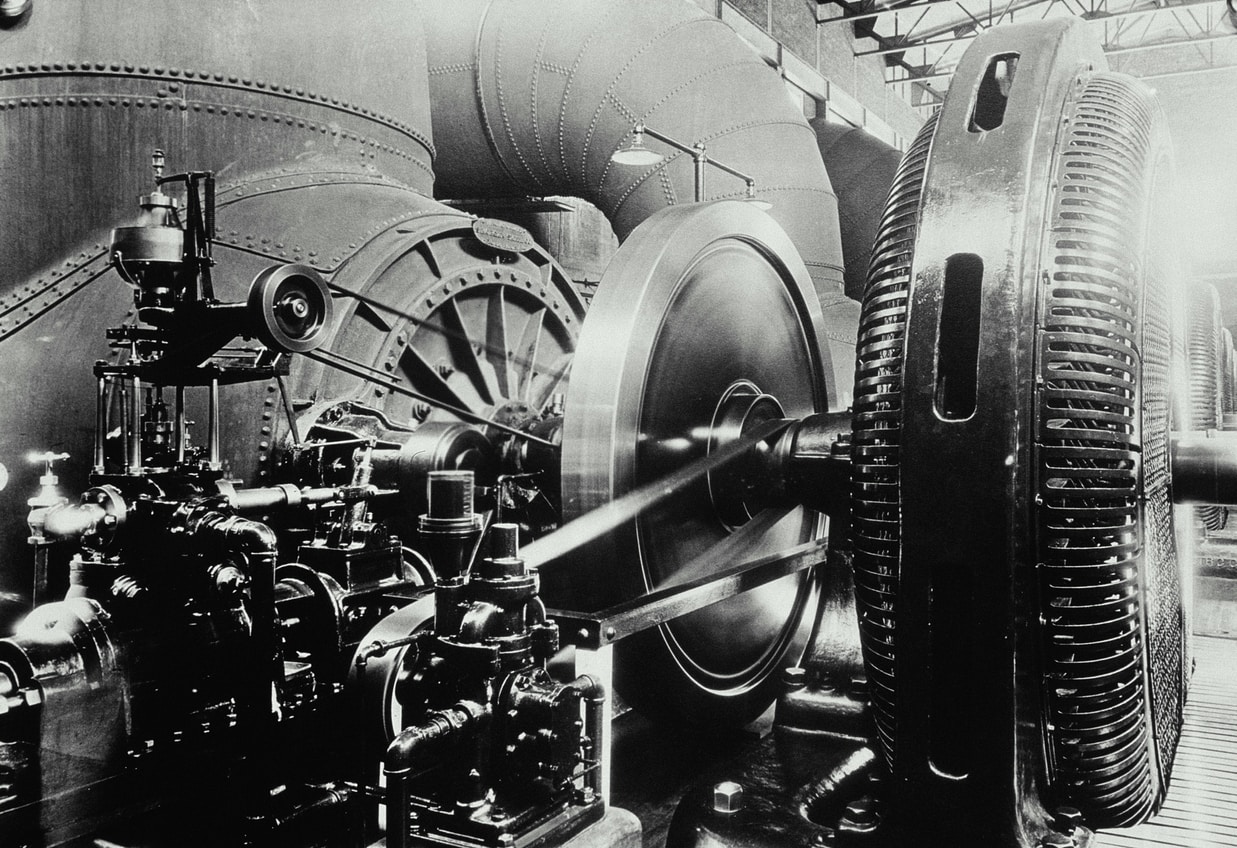

At the heart of the Sim Corder/Harrison Mill lies its most defining feature: a perfectly engineered waterwheel system that converted the kinetic energy of flowing water into mechanical motion. By channeling a nearby stream through carefully designed sluices, engineers created a continuous energy source that powered the mill’s gears, belts, and grinding stones. This seamless conversion of water power into productivity made the mill a beacon of innovation long before electricity reshaped the industrial landscape.

What makes the mill’s design so impressive is its efficiency. Every rotation of the wheel represented a balance between force and control. The builders understood the physics of motion intuitively, using materials such as timber and iron to create a system that was both durable and adaptable. The design required no fuel and produced no waste, showcasing a sustainable approach to energy production that modern engineers continue to admire and study.

Architecture That Withstood the Test of Time

The structure of the Sim Corder/Harrison Mill is as much a marvel as the machinery inside. Crafted from stone foundations and wooden beams, it was built to last. The builders combined functionality with beauty, creating a layout that emphasized balance and stability. The solid walls absorbed vibrations from the moving gears, while the high ceilings allowed for smooth air circulation and easy maintenance of machinery.

Sunlight streamed through expansive, arched windows, illuminating the workspace naturally. This not only reduced the need for artificial lighting but also provided a comfortable environment for workers. Even the placement of doors and windows followed practical reasoning—positioned strategically to align with the movement of water and airflow. The result was a structure that harmonized with its surroundings, embodying both strength and grace.

Modern architects often point to the mill as an early example of sustainable design. Its builders intuitively understood how to make a structure coexist with nature rather than compete against it. That balance between engineering and environment is one of the many reasons the Sim Corder/Harrison Mill remains an enduring masterpiece.

The Mill That Built a Community

Beyond its mechanical excellence, the Sim Corder/Harrison Mill played a pivotal role in shaping local life. It was not just an industrial hub—it was the heart of the community. Farmers brought their grain to be processed, artisans repaired tools in its shadow, and traders met to exchange goods and ideas. The hum of the machinery was the rhythm of progress, echoing across the countryside and signaling opportunity for all.

The mill created a cycle of prosperity. Turning water into productivity, farmers saved time and labor, increased food production, and supported local trade. It became a place where innovation met collaboration—a shared space that brought people together under a common goal of growth and development. Historians often describe it as one of the most influential centers of rural industry, where human connection and technology advanced hand in hand.

Lessons in Sustainable Engineering

For today’s engineers and environmental designers, the Sim Corder/Harrison Mill offers timeless lessons in sustainable innovation. Long before the world began to emphasize renewable energy, this mill demonstrated that efficiency and environmental harmony could coexist. Its water-powered system required no combustion, emitted no pollution, and operated indefinitely with minimal maintenance.

Every mechanism in the mill served a purpose, and nothing went to waste. The builders practiced principles that modern engineers strive to achieve: precision, balance, and respect for natural resources. By studying the mill’s design, we gain insight into how early inventors achieved sustainability without sacrificing performance. The Sim Corder/Harrison Mill reminds us that true innovation doesn’t always depend on advanced technology—it depends on intelligent design and the thoughtful use of what nature provides.